Yes, I’m THAT guy.

I’m the guy you hated in school who was a natural at sight-singing. The guy who tested out of his college ear training courses in record time and never had to show up for those classes. The guy who didn’t have any trouble transcribing things, detecting errors, and hitting tricky intervals on his instrument out of thin air. Because I was the guy who could hear it all in advance.

Yep, that’s right. I have perfect pitch: The ability to identify any note once it’s been played or to sing any requested note on command.

Or at least… I did have it.

Maybe I still do? It’s hard to tell. But for multiple reasons, I’m starting to suspect my perfect pitch is slipping. I’m also starting to suspect whether or not I had perfect pitch at all. And on an even deeper level, I have to wonder if there is even such a thing as “perfect pitch.”

So here’s how this whole journey over the past few years started, and how I’m starting to feel about it…

Part of this involves painting a picture of what my music activities have looked like throughout my life, starting with my childhood (when my family first discovered I had perfect pitch). My parents are both hobby musicians, and I can still remember the sounds of them tuning their guitars on a regular basis. I can remember the various toy xylophones and recorders and makeshift melodicas that didn’t have note names labeled but instead had numbers or colors or such things. I also remember my favorite melodica when I was 6 or 7 years old being tuned roughly in the realm of B-flat major. Yes, I have a freakishly vivid memory. That’s an important point to save for later.

I remember starting on trumpet in 6th-grade band and being super confused. I even asked my teacher off to the side: “I think my trumpet is broken. I’m playing an E but it doesn’t sound like the E my parents play on a guitar, it sounds like a D!” Needless to say, I learned about transposing instruments pretty early, and was assured that my trumpet was just fine.

I was also taking piano lessons at that point, and so I spent a lot of time acquainting myself with electric keyboards. When my family did eventually get a real piano, it wouldn’t stay in tune unless it was tuned a whole step low. That was fine for me. I’d just pretend that piano was like my trumpet. An E on that piano was the same E that my trumpet was. It didn’t get in my way too much.

And amidst all of this, I was playing around with computer notation software for the first time and loving it! I’d spend hours on the computer every day just plugging notes into a staff and hearing them play back to me. Some kids in my generation had Microsoft Paint… I had Musictime Deluxe, and later Finale 2001. And even though I set piano to the side for a while, I stuck with different band instruments and would learn the basics of playing pretty much every instrument I could get my hands on.

All of this to say… for as long as I can remember, I’ve been in an environment saturated with pitch identification in some form or other.

And like I said earlier, I have a good memory. It was only natural for me to remember what an A was supposed to sound like on whatever instrument I was playing. It was the same A that I remembered from yesterday.

So what changed in these past few years?

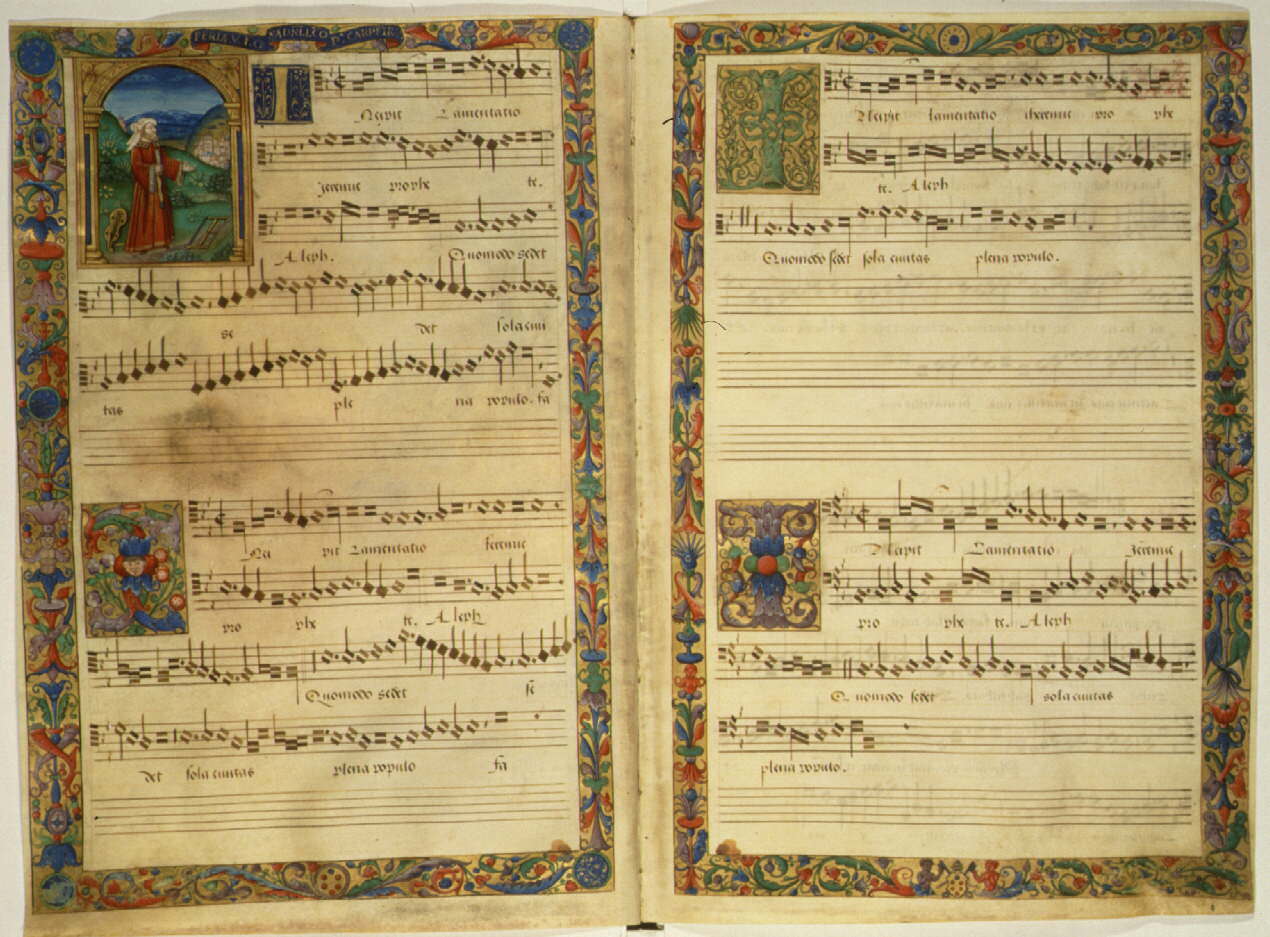

Well, it started a few years ago, where I spent some time singing with some friends in a Renaissance quintet.

A singer with perfect pitch flexes their “perfect pitch muscles” most often doing one particular activity: picking the notes they have to sing out of thin air. We’re often thought of as human pitch-pipes. You’ll see several choral ensembles show off their one or two members with perfect pitch by having them give the starting note instead of playing it on a piano (we really don’t like doing that, side note). So I’ve used my perfect pitch in the past to give starting notes in whatever ensemble I’ve sung in, and have set it aside, at least, consciously, for whatever other musical activities I do.

But there’s an important thing about Renaissance and Baroque ensembles… like my old out-of-tune piano, the pitch sits lower than you’d expect. A modern orchestra usually tunes to A-440 (That is, A in the treble clef staff vibrates at a frequency of 440Hz). Historically, however, the A that Renaissance music was performed in was closer to A-415, a somewhat slower vibration, which makes the pitch roughly a half-step lower than what it used to be.

This means if we were singing a piece in A minor, I’d be hearing it in (almost but not quite) G-sharp minor.

So for several months, the majority of note identification I was doing on the regular… was close to a half-step off from the norm.

Alongside this, starting then, I started putting much more of my effort into teaching as opposed to performing and composing. Instead of sitting immersed in MIDI sounds from Finale or practicing on a freshly-tuned piano or organ, I’m more immersed in the silence of lesson plans, where the sound of that A at exactly 440Hz isn’t nearly as important as it used to be.

So why, really, would I need to remember what that particular A sounded like?

After all, the A at 415Hz was the most useful thing I last flexed my muscles for.

So here lately, more than usual, I’ve been second-guessing every time I’ve tried to identify the key of a song I’m listening to, or been asked to provide a pitch out of the ether. That song is in E minor… wait, is that E minor in 415 or 440? Maybe it’s really E-flat minor, or F minor? Let me check… nope, I was right, it’s E minor. Why was I convinced it was E-flat minor for a moment? There were so many pitches distracting me that I forgot what an E was “supposed” to sound like and how that’s different from an E-flat.

This isn’t having the largest of impacts on me as a musician, of course. I can still sight-sing, hear intervals, transcribe melodies, etc. But the parlor-trick element of perfect pitch—the one that most perfect pitch people use to show off—has become more elusive. Perhaps my memory isn’t as good as it used to be from lack of use.

And that’s where the question comes… is there really such a thing as “perfect pitch,” or it just a freakishly good memory of what those pitches are supposed to sound like?

This seems to be the principle of many online programs designed to “teach” perfect pitch… you listen to a note on a drone for long periods of time, until you can remember what that note is. Eventually, you either remember the sound of multiple notes or use the ear training skills you’ve already developed to figure out the notes around that one note you can regurgitate 75-80% of the time.

So I’ve stopped thinking of perfect pitch as its own innate skill. Maybe it is for some. I’m not a neurologist and couldn’t tell you. But I can say for certain now that it’s not an innate skill for me. It’s just an exercise of memory, remembering what a particular note is “supposed” to sound like (unless you’re playing trumpet, or singing in a Renaissance ensemble, or playing a piano that’s grossly out of tune, or…), and the mental gymnastics attached to all of that, at the end of the day… are they really worth it?

Not necessarily for what I need to do. If I’m composing a piece and type in a starting note that’s tuned to the “wrong” A, then all I have to do is change the note in my score and adjust accordingly. A tuning fork and pitch pipe for performances and rehearsals isn’t all that expensive. And I can’t retune a piano on the spot anyway.

So at the end of the day, I’ve stopped caring about this change in my hearing patterns, and have just started seeing it as a curiosity.

And in some senses… a relief.

Especially if it means never having to worry about being a human pitch pipe.

Leave A Comment